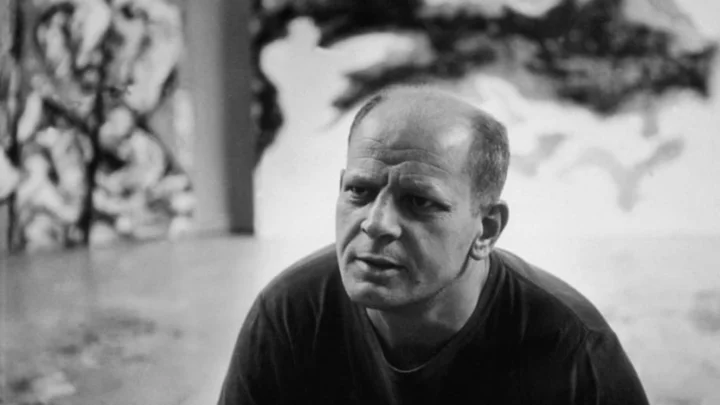

It’s easy to dismiss Jackson Pollock’s No. 5, 1948 as a senseless splatter of paint—but even if you can’t appreciate its aesthetic, this piece of art has a history that’s worth its weight in house paint and stacks of cash. Here are 10 facts about the late artist’s masterpiece.

1. No. 5, 1948 is a key work in the Abstract Expressionist movement.

In the wake of World War II, New York City artists like Jackson Pollock, Barnett Newman, and Willem de Kooning began pushing the boundaries of their paintings in a direction that would be dubbed “Abstract Expressionism” by art critic Robert Coates in 1946. This wave of modern art made New York the center of the art world, thanks in part to the movement's embrace by esteemed collector and patron Peggy Guggenheim. Pollock’s contribution was his drip paintings, including No. 5, 1948.

2. Jackson Pollock used a unique method to make his drips.

Rather than working from an easel, Pollock would place his canvas on the floor and pace around it, applying paint by dripping it from hardened brushes, sticks, and basting syringes. Pollock had only begun experimenting in this form the year before No. 5, 1948’s creation, but his style soon became so signature he was dubbed “Jack the Dripper.”

“On the floor I am more at ease,” Pollock said. “I feel nearer, more part of the painting, since this way I can walk around it, work from the four sides, and literally be in the painting.”

3. No. 5, 1948 is a marker of the birth of “action painting.”

Drip painting came to seen as a form of “action painting,” a term that was coined by American art critic Harold Rosenberg in 1952. In a catalogue for a 1958 exhibition at the The Dallas Museum for Contemporary Arts, Rosenberg said, “Action Painting has to do with self-creation or self-definition or self-transcendence; but this dissociates it from self-expression, which assumes the acceptance of the ego as it is, with its wound and its magic.”

4. Pollock didn’t do any sketches or pre-planning for No. 5, 1948.

Pollock’s works were revolutionary on several levels. For centuries, artists had sketched out or test-run their large-scale paintings. But not Pollock, who was instead guided by emotion and intuition as he wove around his fiberboard base, dropping and flinging paint as his muse demanded. He abandoned brushstrokes in favor of drips and splashes, and set the art world on fire with his impromptu masterworks.

5. He used unconventional paints for No. 5, 1948.

An important element of the drip method was paint with a fluid viscosity that would allow for smooth pouring. This requirement meant traditional oil paints and watercolors were out. Instead, Pollock began experimenting with synthetic gloss enamel paints that were making old-school, oil-based house paints obsolete. Though this clever innovation was praised, Pollock shrugged it off as “a natural growth out of a need.”

6. For a time, No. 5, 1948 was the world’s most expensive painting.

On June 18, 2006, Gustav Klimt’s Adele Bloch-Bauer I sold for $135 million, making it the highest priced painting in the world. Less than five months later, No. 5, 1948 fetched $140 million. In 2011, this title was snatched by one of Paul Cézanne’s Card Players, with a price tag of $250 million. And in 2016, Salvator Mundi—which some believe was painted by Leonardo da Vinci—was purchased for $450.5 million, blowing all other contenders for world’s most expensive painting out of the water by $150 million.

7. No. 5, 1948 is a massive work.

No. 5, 1948 measures in at 8 feet by 4 feet. The Guardian notes that this means each square foot is worth over $4 million.

8. No. 5, 1948 was possibly sold to fund a bid for the Los Angeles Times.

The New York Times reported entertainment tycoon David Geffen may have unloaded No. 5, 1948 in that 2006 sale, along with pieces by Jasper Johns and Willem de Kooning, in an effort to pull together enough capital to purchase the established newspaper. The sale of these three paintings netted $283.5 million. Yet Geffen never did buy the LA Times, even though he tried repeatedly. Once, he even offered $2 billion. In cash.

9. No. 5, 1948 wasn’t only Pollock’s only record breaker.

In 1973, Pollock’s 1952 piece Blue Poles sold for $2 million. While nowhere near as expensive as No. 5, 1948, that figure was enough to make it the highest price paid for a contemporary American work at that time. Sadly, Pollock never saw either of his pieces make art history—a car accident on August 11, 1956, cut his life painfully short.

10. The painting made a cameo in a movie—and was referenced in a song.

No. 5, 1948 appears in the 2015 sci-fi film Ex Machina starring Oscar Isaac and Domhnall Gleeson and directed by Alex Garland. “There was something about what Pollock was trying to do as a painter that had to do with the automatic, to try to paint in an unconscious way, that fitted in a thematic … and actually a literal way … the issues that the film was talking about,” Garland explained Set Decor magazine. “So there was a Jackson Pollock painting specified, discussed in the script as a plot point, as a theme point.” The painting is also name dropped in the song “Going Down” by the Stone Roses: “There she looks like a painting / Jackson Pollock’s No. 5 ... ”

11. No. 5, 1948 and Pollock’s other paintings still mystify a lot of viewers.

While the art critics gush and collectors lay down millions for an auctioned Pollock piece, a good portion of the public is still confounded by the artist’s output 60-plus years later. Every time one of his paintings sells for millions, articles pop up asking why. The short answer is, though his drip paintings may not be accessible, they were seminal, changing the way we think of art itself. They may not be traditionally pretty. But they are both art and art history.

A version of this story ran in 2018; it has been updated for 2023.

This article was originally published on www.mentalfloss.com as 11 Fascinating Facts About Jackson Pollock’s ‘No. 5, 1948’.